Eritrean refugees are one of the main groups in this protest against Israel's hard line on immigration, Tel Aviv, January 5, 2014. (Reuters/Nir Elias)

Hundreds of thousands of Eritreans have fled a repressive dictatorship since 2001. Their small northeast African country, which has a population of 4-5 million and was once touted as part of an African “renaissance,” is one of the largest per capita producers of asylum seekers in the world.

Many languish in desert camps. Some have been kidnapped, tortured and ransomed—or killed—in the Sinai. Others have been left to die in the Sahara or drowned in the Mediterranean. Still others have been attacked as foreigners in South Africa, threatened with mass detention in Israel or refused entry to the United States and Canada under post-9/11 “terrorism bars” based on their past association with an armed liberation movement—the one they are now fleeing.

It’s not easy being Eritrean.

The most horrifying of their misfortunes—the kidnapping, torture and ransoming in Sinai—has generated attention in the media and among human rights organizations, as did the tragic shipwreck off Lampedusa Island in the Mediterranean. But the public response, like that to famine or natural disaster, tends to be emotive and ephemeral, turning the refugees into objects of pity or charity with little grasp of who they are, why they take such risks or what can be done to halt the hemorrhaging.

This is abetted by the Eritrean government, which masks the political origins of these flows by insisting they are “migrants,” not refugees, and no different from those of other poor countries like Eritrea’s neighbor and archenemy, Ethiopia. This fiction is convenient for destination countries struggling with rising ultra-nationalist movements and eager for a rationale to turn Eritreans (and others) away.

But this is not a human—or political—crisis amenable to simplistic solutions. Nor is it going away any time soon.

The Source

Eritrea’s history has been marked by conflict and controversy from the time its borders were determined on the battlefield between Italian and Abyssinian forces in the 1890s. A decade of British rule was followed by federation with and then annexation by Ethiopia. Finally in the 1990s, after a thirty-year war that pitted the nationalists, themselves divided among competing factions, against successive US- and Soviet-backed Ethiopian regimes, Eritrea gained recognition as a state.

Since then Eritrea has clashed with all of its neighbors, climaxing in an all-out border war with Ethiopia in 1998–2000 that triggered a rapid slide into repression and autocracy. The government has survived by conscripting the country’s youth into both military service and forced labor on state-controlled projects and businesses, while relying on its diaspora for financial support, even as it has produced a disproportionate share of the region’s refugees. This paradox underlines the strength of Eritrean identity, even among those who flee.

Eritrea is dominated by a single strong personality: former rebel commander, and now president, Isaias Afwerki. He has surrounded himself with weak institutions, and there is no viable successor in sight, though there are persistent rumors of a committee-in-waiting due to his failing health. Meanwhile, the three branches of government—nominally headed by a cabinet, a National Assembly and a High Court—provide a façade of institutional governance, though power is exercised through informal networks that shift and change at the president’s discretion. There is no organizational chart, nor is there a published national budget. Every important decision is made in secret.

The ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), a retooled version of the liberation army, functions as a mechanism for mobilizing and controlling the population. No other parties are permitted. Nor are non-governmental organizations—no independent trade unions, media, women’s organizations, student unions, charities, cultural associations, nothing. All but four religious denominations have been banned, and those that are permitted have had their leaderships compromised.

Refugees cite this lack of freedom—and fear of arrest should they question it—as one of the main reasons for their flight. But the camps in Ethiopia and Sudan reflect a highly unusual demographic: Most such populations are comprised of women, children and elderly men, but officials of the UN’s High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Ethiopia and Sudan say that among those registering in the camps there, close to half in recent years have been women and men under the age of 25. The common denominator among them is their refusal to accept an undefined, open-ended national service. This, more than any other single factor, is propelling the exodus.

The UNHCR has registered more than 300,000 Eritreans as refugees over the past decade, and many more have passed through Ethiopia and Sudan without being counted. The UNHCR representative in Sudan, Kai Lielsen, told me last year that he thought seventy to eighty percent of those who crossed into Sudan didn’t register and didn’t stay. Thus, a conservative estimate would put the total close to a million. For a country of only four to five million people, this is remarkable. And it is the combination of their vulnerability and their desperation that makes them easy marks.

The Trafficking

For years, the main refugee route ran through the Sahara to Libya and thence to Europe. When that was blocked by a pact between Libya and Italy in 2006, it shifted east to Egypt and Israel. Smugglers from the Arab tribe of Rashaida in northeastern Sudan worked with Sinai Bedouin to facilitate the transit, charging ever-higher fees until some realized they could make far more by ransoming those who were fleeing.

The smugglers-turned-traffickers eventually demanded as much as $40,000-$50,000, forcing families to sell property, exhaust life savings and tap relatives living abroad. As the voluntary flow dried up, they paid to have refugees kidnapped from UN-run camps after identifying those from urban, mostly Christian backgrounds (those most likely to have relatives in Europe and North America).

I spoke with one survivor in Israel last year whose story was typical. Philmon, a 28-year-old computer engineer, fled Eritrea in March 2012 after getting a tip he might be arrested for public statements critical of the country’s national service. Several weeks later, he was kidnapped from Sudan’s Shagara camp, taken with a truckload of others to a Bedouin outpost in the Sinai and ordered to call relatives to raise $3,500 for his release. “The beatings started the first day to make us pay faster,” he told me.

Philmon’s sister, who lived in Eritrea, paid the ransom, but he was sold to another smuggler and ransomed again, this time for $30,000. “The first was like an appetizer. This was the main course,” he said. Over the next month, he was repeatedly beaten, often while hung by his hands from the ceiling. Convinced he could never raise the full amount, he attempted suicide. “I dreamed of grabbing a pistol and taking as many of them as possible, saving one bullet for myself.”

Early on they broke one of his wrists. During many of his forced calls home to beg for money they dripped molten plastic on his hands and back. After his family sold virtually everything they had to raise the $30,000, he was released. But his hands were so damaged he could no longer grip anything. He couldn’t walk and had to be carried into Israel. Because he was a torture victim, he was sent to a shelter in Tel Aviv for medical care. In this regard, he was one of the lucky ones.

For some 35,000 Eritreans who have come to Israel since 2006, each day is suffused with uncertainty, as an anti-immigrant backlash builds. The government calls them “infiltrators,” not refugees, and threatens them with indefinite detention or—what many fear most—deportation to Eritrea. Philmon has moved on to Sweden, where the reception was more welcoming, though there, too, a virulent anti-immigrant movement is growing.

Last year, the Sinai operation began to contract due to a confluence of factors: increased refugee awareness of the risks, the effective sealing of Israel’s border to keep them out and Egyptian efforts to suppress a simmering Sinai insurgency among Bedouin Islamists. But this didn’t stop the trafficking—it just rerouted it.

What I found in eastern Sudan last summer was that Rashaida tribesmen were paying bounties to corrupt officials and local residents to capture potential ransom victims along the Sudan-Eritrea border—and even within Eritrea and Ethiopia—and were holding them within well-defended Rashaida communities there. Such captives would not be counted by government or agency monitors and would not show up at all were it not for the testimony of escapees and relatives.

Last fall, Lampedusa survivors revealed that Libya is becoming another site for ransoming and kidnapping, illustrating that as one door closes, new opportunities arise across a region of weak states and post–Arab Uprising instability. What Sudan and Libya have in common is not the predators but the prey. And the practice is expanding as word spreads of the profits to be had, much as with the drug trade elsewhere. And it will continue to expand as long as there’s a large-scale migration of vulnerable people with access to funds and no coordinated international response to stop it.

Eritrean refugee flows today run in all directions. They’re facilitated by smugglers with regional and, in some cases, global reach. The gangs behind this engage in a range of criminal activities, within which human trafficking is just a lucrative new line of business. Some have ties to global cartels and syndicates. Some have political agendas and fund them through such enterprises. Most are heavily armed.

Under such conditions, a narrowly conceived security response could quickly spin out of control and escalate into a major counterinsurgency, as in the Sinai in Egypt. For weaker states across the Sahel, the risks of ill-thought-out action are infinitely greater.

What Needs to Happen

An effective approach to this crisis would start with education and empowerment of the target population and involve efforts to identify and protect refugees throughout their flight. A key step is the early, uncoerced determination of status according to international standards. This could be coupled with an expansion of incentives to deter onward migration, including education, training, employment and, where appropriate, integration into host communities. But none of this can work without refugee engagement in the process itself.

Then, and only then, would a security operation targeted at the smuggling and trafficking have a chance of success. But it, too, needs to be multidimensional in substance and regional in scope. Each state in this network is acting independently of the others. Sudan has arrested individuals implicated in trafficking, including one police officer, but has not cracked down on corrupt officials or gone into Rashaida communities to take down the ringleaders. Ethiopia has instituted security measures within the refugee camps on its northern border but is not working with Sudan on cross-border movement. Egypt has launched military operations in the Sinai where the torture camps are situated, but the announced aim is to break up the Islamist insurgency—the government denies trafficking is taking place. A coordinated initiative would start with a conference of affected states, and it would have to be supported by donor states and appropriate agencies (Interpol among them), not only in terms of aid but also intelligence, logistics, coordination and communication.

But if the trafficking operations are truly to be rolled up, the marginalized populations from which they arise and on which they depend need to be offered sufficient incentives to withdraw support for the criminals. This means access to resources, economic alternatives to off-the-books trading, involvement in the local political process, education for their children and more. These people need to be made stakeholders in the states where they live, which is not the case today for the Sinai Bedouin or the Sudan-based Rashaida or most of the other groups involved in trans-Sahel smuggling.

Meanwhile, to dry up this particular supply of prey, political change is needed at the source, in Eritrea. That means, at a minimum, opening up the political system and the economy, limiting (not necessarily ending) national service, releasing political prisoners, implementing the long-stalled constitution and ending controls on travel so those who do want to go abroad as migrant workers can do so without illegally crossing borders and going through illicit smuggling networks.

The most important thing the United States can do to facilitate this process is convince Ethiopia to back off the border dispute that centers on a frontier town, Badme, and accept in practice—not just rhetorically—the 2002 Border Commission ruling that went in Eritrea’s favor.

Ethiopia’s intransigence on this issue—and US inaction—has long been the Asmara regime’s most powerful argument for keeping the lid on all forms of dissent. Eritreans will simply not trust Washington—or Addis Ababa—until they see some evidence of good faith.

Hundreds of thousands of Eritreans have fled a repressive dictatorship since 2001. Their small northeast African country, which has a population of four to five million and was once touted as part of an African “renaissance,” is one of the largest per capita producers of asylum seekers in the world.

Many languish in desert camps. Some have been kidnapped, tortured and ransomed—or killed—in the Sinai. Others have been left to die in the Sahara or drowned in the Mediterranean. Still others have been attacked as foreigners in South Africa, threatened with mass detention in Israel or refused entry to the United States and Canada under post-9/11 “terrorism bars” based on their past association with an armed liberation movement—the one they are now fleeing.

It’s not easy being Eritrean.

The most horrifying of their misfortunes—the kidnapping, torture and ransoming in Sinai—has generated attention in the media and among human rights organizations, as did the tragic shipwreck off Lampedusa Island in the Mediterranean. But the public response, like that to famine or natural disaster, tends to be emotive and ephemeral, turning the refugees into objects of pity or charity with little grasp of who they are, why they take such risks or what can be done to halt the hemorrhaging.

This is abetted by the Eritrean government, which masks the political origins of these flows by insisting they are “migrants,” not refugees, and no different from those of other poor countries like Eritrea’s neighbor and archenemy, Ethiopia. This fiction is convenient for destination countries struggling with rising ultra-nationalist movements and eager for a rationale to turn Eritreans (and others) away.

But this is not a human—or political—crisis amenable to simplistic solutions. Nor is it going away any time soon.

The Source

Eritrea’s history has been marked by conflict and controversy from the time its borders were determined on the battlefield between Italian and Abyssinian forces in the 1890s. A decade of British rule was followed by federation with and then annexation by Ethiopia. Finally in the 1990s, after a thirty-year war that pitted the nationalists, themselves divided among competing factions, against successive US- and Soviet-backed Ethiopian regimes, Eritrea gained recognition as a state.

Since then Eritrea has clashed with all of its neighbors, climaxing in an all-out border war with Ethiopia in 1998-2000 that triggered a rapid slide into repression and autocracy. The government has survived by conscripting the country’s youth into both military service and forced labor on state-controlled projects and businesses, while relying on its diaspora for financial support, even as it has produced a disproportionate share of the region’s refugees. This paradox underlines the strength of Eritrean identity, even among those who flee.

Eritrea is dominated by a single strong personality: former rebel commander, and now president, Isaias Afwerki. He has surrounded himself with weak institutions, and there is no viable successor in sight, though there are persistent rumors of a committee-in-waiting due to his failing health. Meanwhile, the three branches of government—nominally headed by a cabinet, a National Assembly and a High Court—provide a façade of institutional governance, though power is exercised through informal networks that shift and change at the president’s discretion. There is no organizational chart, nor is there a published national budget. Every important decision is made in secret.

The ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), a retooled version of the liberation army, functions as a mechanism for mobilizing and controlling the population. No other parties are permitted. Nor are non-governmental organizations—no independent trade unions, media, women’s organizations, student unions, charities, cultural associations, nothing. All but four religious denominations have been banned, and those that are permitted have had their leaderships compromised.

Refugees cite this lack of freedom—and fear of arrest should they question it—as one of the main reasons for their flight. But the camps in Ethiopia and Sudan reflect a highly unusual demographic: Most such populations are comprised of women, children and elderly men, but officials of the UN’s High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Ethiopia and Sudan say that among those registering in the camps there, close to half in recent years have been women and men under the age of 25. The common denominator among them is their refusal to accept an undefined, open-ended national service. This, more than any other single factor, is propelling the exodus.

The UNHCR has registered more than 300,000 Eritreans as refugees over the past decade, and many more have passed through Ethiopia and Sudan without being counted. The UNHCR representative in Sudan, Kai Lielsen, told me last year that he thought seventy to eighty percent of those who crossed into Sudan didn’t register and didn’t stay. Thus, a conservative estimate would put the total close to a million. For a country of only four to five million people, this is remarkable. And it is the combination of their vulnerability and their desperation that makes them easy marks.

The Trafficking

For years, the main refugee route ran through the Sahara to Libya and thence to Europe. When that was blocked by a pact between Libya and Italy in 2006, it shifted east to Egypt and Israel. Smugglers from the Arab tribe of Rashaida in northeastern Sudan worked with Sinai Bedouin to facilitate the transit, charging ever-higher fees until some realized they could make far more by ransoming those who were fleeing.

The smugglers-turned-traffickers eventually demanded as much as $40,000-$50,000, forcing families to sell property, exhaust life savings and tap relatives living abroad. As the voluntary flow dried up, they paid to have refugees kidnapped from UN-run camps after identifying those from urban, mostly Christian backgrounds (those most likely to have relatives in Europe and North America).

I spoke with one survivor in Israel last year whose story was typical. Philmon, a 28-year-old computer engineer, fled Eritrea in March 2012 after getting a tip he might be arrested for public statements critical of the country’s national service. Several weeks later, he was kidnapped from Sudan’s Shagara camp, taken with a truckload of others to a Bedouin outpost in the Sinai and ordered to call relatives to raise $3,500 for his release. “The beatings started the first day to make us pay faster,” he told me.

Philmon’s sister, who lived in Eritrea, paid the ransom, but he was sold to another smuggler and ransomed again, this time for $30,000. “The first was like an appetizer. This was the main course,” he said. Over the next month, he was repeatedly beaten, often while hung by his hands from the ceiling. Convinced he could never raise the full amount, he attempted suicide. “I dreamed of grabbing a pistol and taking as many of them as possible, saving one bullet for myself.”

Early on they broke one of his wrists. During many of his forced calls home to beg for money they dripped molten plastic on his hands and back. After his family sold virtually everything they had to raise the $30,000, he was released. But his hands were so damaged he could no longer grip anything. He couldn’t walk and had to be carried into Israel. Because he was a torture victim, he was sent to a shelter in Tel Aviv for medical care. In this regard, he was one of the lucky ones.

For some 35,000 Eritreans who have come to Israel since 2006, each day is suffused with uncertainty, as an anti-immigrant backlash builds. The government calls them “infiltrators,” not refugees, and threatens them with indefinite detention or—what many fear most—deportation to Eritrea. Philmon has moved on to Sweden, where the reception was more welcoming, though there, too, a virulent anti-immigrant movement is growing.

Last year, the Sinai operation began to contract due to a confluence of factors: increased refugee awareness of the risks, the effective sealing of Israel’s border to keep them out and Egyptian efforts to suppress a simmering Sinai insurgency among Bedouin Islamists. But this didn’t stop the trafficking—it just rerouted it.

What I found in eastern Sudan last summer was that Rashaida tribesmen were paying bounties to corrupt officials and local residents to capture potential ransom victims along the Sudan-Eritrea border—and even within Eritrea and Ethiopia—and were holding them within well-defended Rashaida communities there. Such captives would not be counted by government or agency monitors and would not show up at all were it not for the testimony of escapees and relatives.

Last fall, Lampedusa survivors revealed that Libya is becoming another site for ransoming and kidnapping, illustrating that as one door closes, new opportunities arise across a region of weak states and post–Arab Uprising instability. What Sudan and Libya have in common is not the predators but the prey. And the practice is expanding as word spreads of the profits to be had, much as with the drug trade elsewhere. And it will continue to expand as long as there’s a large-scale migration of vulnerable people with access to funds and no coordinated international response to stop it.

Eritrean refugee flows today run in all directions. They’re facilitated by smugglers with regional and, in some cases, global reach. The gangs behind this engage in a range of criminal activities, within which human trafficking is just a lucrative new line of business. Some have ties to global cartels and syndicates. Some have political agendas and fund them through such enterprises. Most are heavily armed.

Under such conditions, a narrowly conceived security response could quickly spin out of control and escalate into a major counterinsurgency, as in the Sinai in Egypt. For weaker states across the Sahel, the risks of ill-thought-out action are infinitely greater.

What Needs to Happen

An effective approach to this crisis would start with education and empowerment of the target population and involve efforts to identify and protect refugees throughout their flight. A key step is the early, uncoerced determination of status according to international standards. This could be coupled with an expansion of incentives to deter onward migration, including education, training, employment and, where appropriate, integration into host communities. But none of this can work without refugee engagement in the process itself.

Then, and only then, would a security operation targeted at the smuggling and trafficking have a chance of success. But it, too, needs to be multidimensional in substance and regional in scope. Each state in this network is acting independently of the others. Sudan has arrested individuals implicated in trafficking, including one police officer, but has not cracked down on corrupt officials or gone into Rashaida communities to take down the ringleaders. Ethiopia has instituted security measures within the refugee camps on its northern border but is not working with Sudan on cross-border movement. Egypt has launched military operations in the Sinai where the torture camps are situated, but the announced aim is to break up the Islamist insurgency—the government denies trafficking is taking place. A coordinated initiative would start with a conference of affected states, and it would have to be supported by donor states and appropriate agencies (Interpol among them), not only in terms of aid but also intelligence, logistics, coordination and communication.

But if the trafficking operations are truly to be rolled up, the marginalized populations from which they arise and on which they depend need to be offered sufficient incentives to withdraw support for the criminals. This means access to resources, economic alternatives to off-the-books trading, involvement in the local political process, education for their children and more. These people need to be made stakeholders in the states where they live, which is not the case today for the Sinai Bedouin or the Sudan-based Rashaida or most of the other groups involved in trans-Sahel smuggling.

Meanwhile, to dry up this particular supply of prey, political change is needed at the source, in Eritrea. That means, at a minimum, opening up the political system and the economy, limiting (not necessarily ending) national service, releasing political prisoners, implementing the long-stalled constitution and ending controls on travel so those who do want to go abroad as migrant workers can do so without illegally crossing borders and going through illicit smuggling networks.

The most important thing the United States can do to facilitate this process is convince Ethiopia to back off the border dispute that centers on a frontier town, Badme, and accept in practice—not just rhetorically—the 2002 Border Commission ruling that went in Eritrea’s favor.

Ethiopia’s intransigence on this issue—and US inaction—has long been the Asmara regime’s most powerful argument for keeping the lid on all forms of dissent. Eritreans will simply not trust Washington—or Addis Ababa—until they see some evidence of good faith.

It is often forgotten that Isaias Afwerki received military training in China in the 1960’s

It is often forgotten that Isaias Afwerki received military training in China in the 1960’s

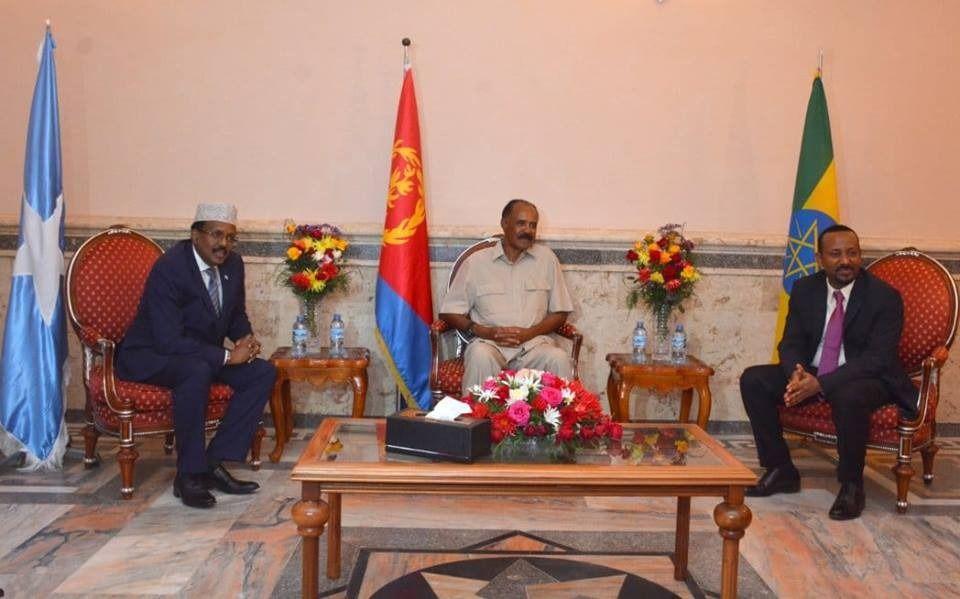

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (R), Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki (C) and Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo pose for a picture in Asmara, Eritrea on January 26, 2020./ PHOTO Courtesy: Abiy Ahmed – Twitter

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (R), Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki (C) and Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo pose for a picture in Asmara, Eritrea on January 26, 2020./ PHOTO Courtesy: Abiy Ahmed – Twitter

Detail of FAO Desert Locust Movements, Aug 2019 – Feb 2020

Detail of FAO Desert Locust Movements, Aug 2019 – Feb 2020