A photo taken on July 22, 2018 shows a general view of Old Massawa with the port and the train tracks that leads to the Eritrean capital Asmara.

A stranger visiting the city won’t sense that anything is amiss. Outwardly, nothing suggests that this is one of the most insular dictatorships in the world, the North Korea of Africa. President Isaias Afwerki has ruled the country with an iron hand for 25 years. In Afwerki’s Eritrea, men serve in the army from age 17 until as late as age 50. Until recently, soldiers deployed along the borders were under orders to shoot anyone trying to flee to one of the neighboring countries. And throughout Eritrea, citizens are entangled in an extensive government-run network of informers: Students betray friends who have deserted the army; housewives inform on neighbors who criticize the regime and so on.

But there’s no hint of any of this in the streets. The only indication that life here is, after all, not as good as it may seem, is the lack of material goods. In the stores and markets I encounter the same products time and again. Bananas, toilet paper, mineral water. There are few clothing stores. Some fruits and vegetables are available in the main market, and old spare parts from cars and other items are on display on sidewalks, but there’s no doubt that in comparison to other cities in Africa, the range of products for sale is limited. With insularity comes dearth.

Next to the market, in the very heart of the city, is the notorious Karsheli Prison, which has both political and former military inmates. Actually, Eritreans often refer to their country as “one big prison.” No one knows how many people are imprisoned in Eritrea, but according to reports from the United Nations and other international organizations, 14,000 people are incarcerated in military prisons alone. Inside Karsheli, which is surrounded by cafés and private residences, inmates undergo torture, according to refugees in exile. Eritrea has a particularly brutal way of eliminating opponents of the regime: They’re thrown into shipping containers under the broiling sun and left to die from heat and thirst.

Karsheli Prison, in the heart of Asmara, Eritrea’s capital. Tamara Baraaz

Karsheli Prison, in the heart of Asmara, Eritrea’s capital. Tamara Baraaz

ISIS and civil war

After half a year of trying, I was informed that I would receive a visa to visit Eritrea. I wanted to see close up the circumstances that have sparked the waves of departure – what has prompted what seems like an entire generation of young people to turn their back on their homeland and scatter far and wide.

There’s something almost biblical in the scale of this exodus and in the dangers that lurk for the escapees afterward. Wherever they turn, Eritrean refugees are in existential danger. Many set their sights on Libya. Some have been caught by ISIS, some made it onto boats to attempt the perilous journey to Europe. Others escaped to Sudan and South Sudan, just as civil war erupted there. Those who headed for Egypt discovered that criminal organizations in Sinai have made a habit of kidnapping refugees, torturing them and demanding a ransom from their families for their release. Tens of thousands of Eritreans entered Israel from Sinai until the high barbed-wire border fence between it and Israel was erected some six years ago.

The visa came and I’m here at last, in Asmara. As I expected, it’s not easy to engage random citizens in conversation; Eritreans are naturally reticent and admit that they don’t tend to confide in strangers. When you add the fear and terror fomented by the state authorities, it’s easy to understand why no one is in a hurry to get into a candid conversation.

To break into the expected circle of silence, I’d been in contact earlier with representatives of the Eritrean underground – a network of clandestine movements and organizations. As I make my way along the streets of the capital to meet my liaison person, Tesfai (the names of all interviewees here have been changed for their protection), I notice I’m being followed. Tesfai explains: “That person has been following us in order to make sure that other people were not following us. He stayed around to observe, so that if someone should decide to ‘disappear’ me, they’ll at least know where it happened.”

The two men both belong to the Eritrean Liberation Democratic Movement, which aims to create “democracy, justice and a flourishing future in our country,” according to the group’s Facebook page. Abroad, its members openly work to advance their cause; here in Asmara, where even the slightest suspicion of criticism of the regime can land you in jail indefinitely, all their activity takes place underground.

Tesfai, who’s in his 20s, points toward the street I came from: “Do you see that building? In the past there was a government office there, and below it was a cellar with prisoners. When the neighbors found out what was going on there, the prison was moved elsewhere and the cellar was rented out. Every house here could be a makeshift jail.” Many of the people who disappeared, he adds, ended up in those jails, some of them in the basements of apartment buildings.

Just a few days earlier, Tesfai relates, agents of the regime arrested a group of young people in a bar. The charge: unlawful assembly. According to him, any gathering of more than five people is forbidden in Eritrea, but the law is enforced arbitrarily. The regime doesn’t usually intervene in cases involving family celebrations.

“They’re afraid of groups that will conspire to topple the government,” Tesfai explains. “But young people won’t give up their social life. People take the risk. In this case, people in civilian clothes showed up and announced that everyone was under arrest for unlawful assembly. No one has seen them since, and no one knows the real reason [they were apprehended], either.”

A street in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea. Maheder Haileselassie Tadese / AFP

A street in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea. Maheder Haileselassie Tadese / AFP

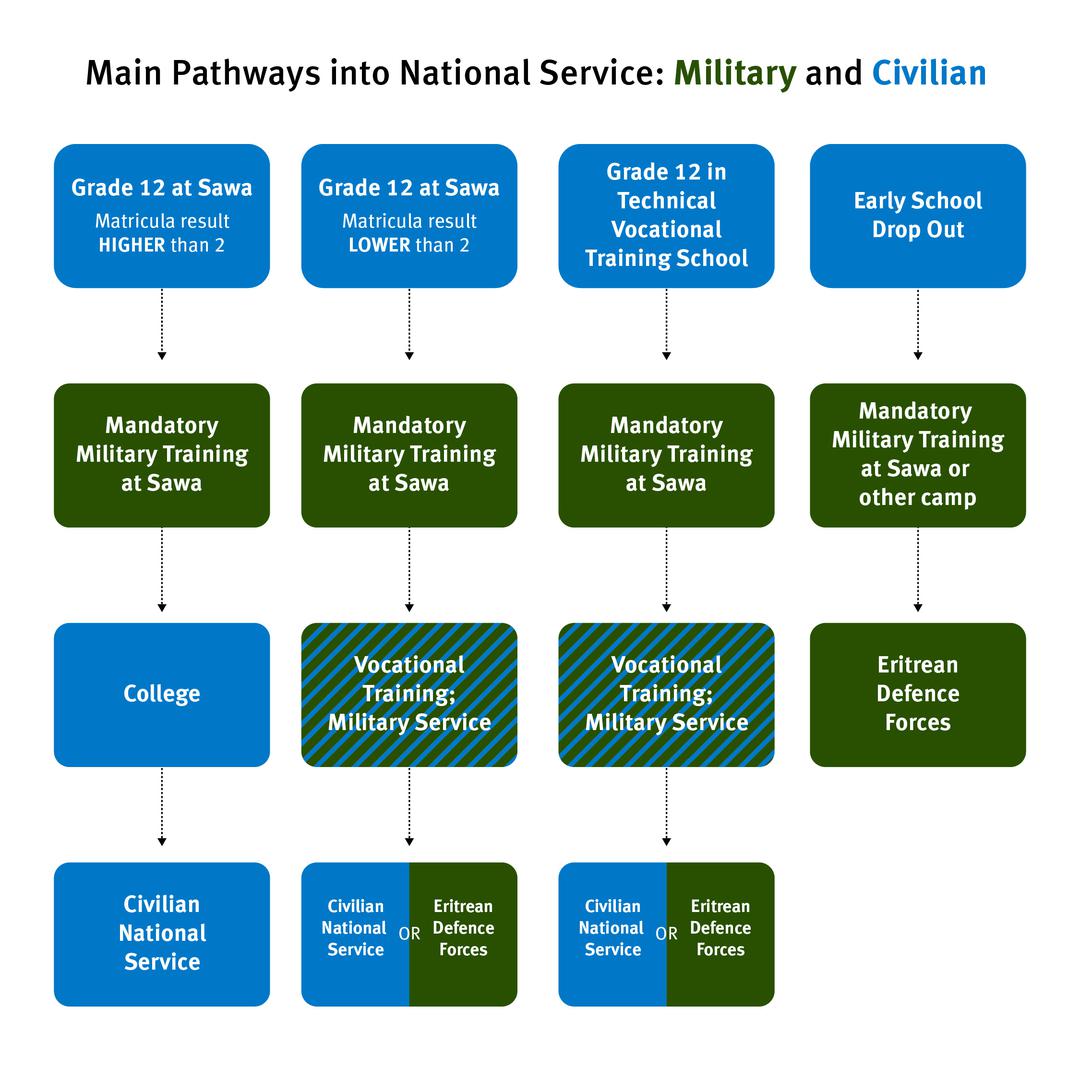

Disappointing peace

How did Eritrea become a dictatorship that’s being abandoned by its citizens? Until the early 1990s the country, which has a population of about five million today, was still part of Ethiopia. In 1993, after waging a prolonged guerrilla war, the Eritreans dissociated themselves from the Addis Ababa government and gained independence. But the disputes didn’t end there. The struggle for independence morphed into a protracted conflict over control of areas along the two countries’ borders. In 1998, when a particularly violent confrontation broke out between them, President Afwerki declared that citizens would be subject to lengthy, mandatory military service – even up until the age of 50.

As the confrontation continued, there were increasing signs that the country was shifting to a regime of one-man rule. Things took a turn for the worse in 2001, when a group of members of the opposition and journalists publicly called for democratic reforms. In response, the president’s loyalists arrested everyone in the group – they are still categorized as missing persons. Since then, the situation has only deteriorated: Independent media outlets were shut down, some religious streams were outlawed, among them Jehovah’s Witnesses. For example, in 2017 the government imposed a ban on Muslim girls wearing a veil to school, on teaching religious subjects and on gender-separated classes. Ultimately, public criticism of the government was prohibited. Eritrea grew ever more insular and eventually became one of the world’s major exporters of refugees.

Last summer, there was a surprising development: After nearly three decades of conflict, Eritrea and Ethiopia signed a peace agreement. Families that had been separated by the border for so long were reunited. Foreign investors and tourists discovered that Eritrea was starting to issue visas and to show initial signs of openness. Swept up by euphoria, Eritreans hoped that the protracted mandatory military service would also be cancelled.

That was eight months ago. Photographs of President Afwerki with his Ethiopian counterpart Sahle-Work Zewde during the reconciliation talks can still be seen in restaurants and shops in Asmara, but the hope for any real change has been largely dashed. Military service was not abbreviated. The human rights situation remains dire. Expectations have been disappointed with respect to any mass return of Eritreans from self-imposed exile. In fact, the opposite has occurred: The flow of people fleeing the country increased.

At present, a large number of Eritreans continue to perform what is in essence, at least for men, open-ended military service. Some are assigned to combat duty near the border with Ethiopia, some are posted to office jobs and many are forced to engage in Sisyphean manual labor in the service of the state in mines, construction, paving of roads and so on. They receive a monthly allowance equivalent to 200 shekels ($55), but are not allowed to take another job. For most of the year they are unable to see their families.

A soldier’s date of discharge is decided arbitrarily by a commanding officer. Service can indeed last until the age of 50, but many are released after one or two decades. Bribery can play a crucial role in securing an early release, too. But even when a soldier is discharged, he can be mobilized again by law at an officer’s whim.

Preference for death

Just over a year ago, I visited Bor, a small town in South Sudan. Not long before, it had been the site of some of the bloodiest fighting during the civil war that broke out in the fledgling state in 2013. The presence of Eritrean refugees was immediately noticeable at the time. Many parts of South Sudan were on the brink of starvation, but the Eritreans seemed to have found their place. I asked some of them why they had come to a place whose local residents had until recently been burying the victims of the war. “We would rather die here than go back to our country,” they told me.

Tekeste, whom I meet in Asmara, also fled to Sudan, but is now back in his native land. He asks me whether I like Eritrea. It’s nice here, I reply, the streets are quiet and pleasant. “That’s because all the young people have left,” he says. “This country has emptied out. The situation here is crap.” A friend immediately interrupts and advises him to be quiet, but Tekeste continues: “She should know what’s going on here, so that she can share it with the rest of the world. Someone has to know about the situation here – that it’s all one big lie.”

When Tekeste finished high school, the dictatorship had been entrenched for two decades. He knew very well what lay in store: that he had to choose between devoting his best years to the army, or leave Eritrea. He made it across the border to a neighboring country but was eventually caught there, along with other refugees, and deported back to Eritrea.

A café in Asmara, Eritrea. Veronique DURRUTY / Gamma-Rapho

A café in Asmara, Eritrea. Veronique DURRUTY / Gamma-Rapho

Back home, Tekeste was immediately jailed as a deserter. “We were 400 prisoners in one cell,” he recalls. “It was so crowded you couldn’t lie down. There was also a shortage of water. Once every three weeks, each inmate received a liter of water so he could shower. Other than that, inmates didn’t shower.”

According to a UN report, the families of soldiers who flee Eritrea are also liable to be severely punished. In some cases, they will lose the right to receive food-ration coupons. The coupons are used to purchase the basic commodities that are available once a month at government-run centers, and thus constitute the basis of subsistence for many families. In the past, loss of coupons was sometimes accompanied by a steep fine; nonpayment led to arrest and incarceration.

But the price of lengthy military service is also paid by families of soldiers who obey the law; such families are doomed to a life of poverty and only get to see their loved one after long periods of time. Binti has lived for years without her husband, who was inducted early on in their marriage. Every month he sends her a pittance equivalent to 125 shekels – about 60 percent of the allowance he gets – an amount that condemns her to extreme poverty.

“He gets one month of leave a year,” Binti explains, “and the rest of the time I don’t see him. In the 20 years of our marriage, we have spent a total of two years together. We had a daughter early on, and now she has also reached draft age. She was sent to serve in another city and I was left alone, to live off the small amount my husband sends me.”

How has Eritrea’s regime succeeded in subjecting the populace to its whims? Actually, for one particular class in the country – for example, business owners with connections to the regime – life isn’t so bad. Impressive buildings, cafés and restaurants line the capital’s main boulevard. In the evening the street comes alive and well-dressed young people come to guzzle beer and sip espresso. During the day, groups of cyclists go by – bicycling is the country’s leading sport. Quiet, peaceful streets branch off the boulevard. Yonas, a local resident, says it’s safe to walk around. “If someone finds a wallet with cash, you can be sure he’ll turn it in to a police station,” he says.

But the ostensible normality of the main boulevard and surrounding streets is deceptive. The state preserves stability through a national network of informants that keeps everyone intimidated. “People in Asmara will always assume that they are being spied on,” says Abraham Zere, an Eritrean journalist who lives in the United States, in a phone interview. “There’s a great deal of below-the-surface monitoring going on, and people are aware of the danger. So, despite the dire situation, when you ask someone how he is, he’ll say ‘Fine’ and smile.”

Spying on friends

A 2015 report of the UN’s Human Rights Council describes Eritrea’s domestic espionage network as a large, ramified body that encroaches on all spheres of life. The authorities recruit informants ceaselessly and in large numbers, so everyone lives under constant fear of being under surveillance. “In Eritrea everyone is a spy, local housewives, farmers, etc.,” the report quotes a witness as saying. “So they know when you arrive and when you leave. Your own neighbors report you to the authorities.”

Another young man testified that someone had asked him to spy on his fellow students: “Whatever information I gave him, he already knew of it. I came to understand that I was not the only one ‘on the ground.’ Other people could also know what I was doing… In a room with 10 people, maybe three could be spies. These people that are mandated to do surveillance work do it for a number of reasons: easy money, little labor, exemption from national service.”

Tesfai, the underground member, says that years ago, intelligence personnel attempted to recruit him too to spy on friends. “They asked me whether I would be willing to do everything for my country,” he recalls. “I replied that of course I would. Then they asked if I would report on an offense that could harm my country, and I understood what they were after. I replied that I would be ready to report murder or theft or any offense that is harmful to society, but I made it clear that I had no intention of reporting on my friends’ opinions or on remarks of acquaintances about the regime.” He was lucky: They authorities left him alone. Others paid for refusal with incarceration.

A market in Asmara. YokoAziz 2 / Alamy Stock Photo

A market in Asmara. YokoAziz 2 / Alamy Stock Photo

The UN report notes that the Eritrean espionage network operates overseas, too; staff at its embassies even try to recruit collaborators among the exiles. In return, they promise to provide jobs and assistance in various matters. One of the sanctions used against opposition activists who voice criticism abroad is loss of rights of their family members still in Eritrea, and in some cases their incarceration. Such measures explain the fear of Eritrean refugees to critique the regime or talk about the crimes they’ve witnessed.

According to Tesfai, “It’s impossible to truly hide from the regime’s network of informants. Everyone knows everyone. You’re better off being open about most things and hiding only what is explicitly forbidden. In Eritrea everyone is slightly in favor of the government and slightly against it. If you praise the regime during a family event, everyone will agree with you and praise the president. If you complain about the situation, they will accept that, too, but the conversation will end when someone says, ‘So go demonstrate on the streets, let’s see you.’ But still, family is family. No one will inform on you for things you say at home. The authorities have succeeded in destroying the basic trust between people, but not in destroying the family unit.”

And if someone in the family is a government informer? Tesfai says that no one sells out relatives. “In a case like that, the informant might say that he knows about my activity and will warn me that if I persist with it he will not be able to protect me. But still, in Eritrea the family is the strongest thing.”

A byproduct of the omnipresent network of surveillance is that people don’t allow themselves to feud with neighbors or acquaintances. Says Tesfai: “You need to avoid confrontations and make sure that everyone feels you are on their side. If there is bad blood between you and an acquaintance, he can exploit [the memory of] that wedding party where you were drunk and complained about the regime.” Tesfai says he can be truly open only with close friends whom he’s gotten to know over a long, gradual period: “I can count them on fewer than the fingers of one hand.”

His own master

It’s been four months since Afwerki last addressed the nation. The hope was that in that speech, he would announce abridgement of military service, but he didn’t even mention it. According to Tesfai, “The thinking is that the president is afraid to cancel the eternal military service, because then he will have to cope with frustrated young people who have never done anything in life other than being in the military.”

Tadesse recently left the army after two decades. “I wasn’t officially discharged,” he explains. “I just told the commander that I had made my contribution to the state and that I was going. He didn’t object.” Tadesse spent his first years of service along the border, in the period when the confrontation with Ethiopia flared up into outright hostilities. As a young soldier, he witnessed brutal battles. “We lost many comrades-in-arms,” he relates. “Things were hard in the years after the fighting, too. Conditions in the army were awful, no different from the prisons, except maybe that you have more room to walk around.”

Having spent almost his whole adult life in the army, Tadesse, like the rest of his comrades-in-arms, never went to university or held a job. Inexperienced and apprehensive, he found himself competing in a tough job market after his discharge. The other job-seekers he encountered were former soldiers, students who were exempted from military service thanks to their high grades and fortunate young people who weren’t drafted because their families are well connected. But Tadesse got lucky and landed a job. It’s low paying, but the wages are higher than what he got in the army. What’s most important, he says, is that now he is his own master.

“My friends are still in the army,” Tadesse explains. “They don’t know anything else and they simply aren’t capable of leaving. It makes no difference to them that since the peace accord, monitoring of deserters has decreased. In the past few months many checkpoints have been removed, and discharge or exemption documents aren’t checked as they were in the past. But that doesn’t really help people who think they have nothing to come back to and say they won’t find work.”

When I met Tadesse a few weeks ago, he believed that the authorities would ease up gradually and loosen the reins. But since then, pessimistic reports have been making the rounds among the Eritrean community abroad. “We are in regular contact with residents of Asmara,” says Dr. Daniel Mekonnen, director of the Eritrean Law Society, who has lived since 2001 in exile in Switzerland. “We are being told that the checkpoints have been put back in place and that all departures from Asmara are being monitored. We understand that military forces have been beefed up and are on standby, but it’s not really clear to us why.”

Old cars in the streets of Eritrea’s capital.

Old cars in the streets of Eritrea’s capital.

As a district court judge in Asmara 20 years ago, Mekonnen explains in a phone call, he already saw signs of a grim future in Eritrea. “You could see that the system was moving toward dictatorship,” he says. “Already then, the court’s independence began to be curtailed, and I came under heavy pressure to rule in favor of the government’s interests in certain cases, or to join the ruling party.”

Mekonnen is openly and frequently critical of the regime. Even though he left his homeland long ago, he still gets threats via telephone and the social networks. “The most frightening incident was three years ago, in Geneva,” he recalls, “at a demonstration against the conclusions of a UN report on Eritrea that caused a big storm. Two Eritreans at the demonstration started to attack me. I was beaten and battered, but I ran to the UN headquarters, and was protected by the guards. I filed a complaint with the police, but they didn’t take it seriously. In general, we find that countries that have become Eritrean diasporas don’t want to intervene and help.”

The atmosphere on Asmara’s main boulevard betrays no signs of the tensions and experiences described by Dr. Mekonnen. Eritreans are quite sociable. The people in cafés are affable, take an interest when they meet foreigners, and repeatedly offer to pay for a visitor’s coffee or meal, according to the norms of local hospitality.

One man I met, named Bruno, explains that “the cafés are indeed full of people, but it only looks as though they are there to enjoy themselves. Actually, it’s where they run their business from. Most of the day they’re stuck doing their public work, in the army or in the service of the state, but it’s impossible to subsist on what the regime pays. They’re not allowed to start a business of their own, so they take long lunch breaks and manage their secret projects from the cafés. That’s also why nothing gets done in government offices. It’s the only revolt people allow themselves [to wage].”

As the days go by during my visit, the discrepancy between the initial impression created by the city’s streets and the actual reality becomes more acute. In fact, it’s possible to sense echoes of the dictatorship resonating in every sphere of life. From my conversations I realize that the lengthy military service and the mass exodus of young men have fundamentally unhinged the social order here.

“One of the consequences of what’s happening is that there are fewer couple relationships here,” Tesfai notes. “People try to marry off their children and help one another, but in the end most of my friends are single. They are people in their 30s who are simply unable to establish a family on the money they get for their military service. They don’t have a life outside the army.”

Tekeste agrees: “Military service has destroyed all male-female ties. Women are conscripted, too, but are discharged if they become pregnant, even if that is not officially stated in the law. Some women decide to become pregnant at any price in order to be exempted from service. Asmara is full of single mothers. Men who earn so little are afraid that they will be required to pay child support, and in Eritrea paternity testing is banned by law. This whole situation creates problems.”

In addition to the impact on interpersonal relations, the despotic rule and the lengthy mobilization are also harmful to the country’s economy. Experts point to the limited scope of agriculture in Eritrea. Besides the droughts and an abundance of mine fields, the country is also affected by a labor shortage: With so many working-age men serving in the army and many others in exile, people able to work the land are in short supply.

Economically, an Eritrean family is beholden to the government in almost every realm, above and beyond the food-coupons system. Many professionals are still at the beck and call of the army. This affects physicians and teachers, and also influences the construction industry, road-building and other infrastructure projects – all carried out by forced laborers drafted as soldiers. This situation of absolute dependence is instrumental in allowing the regime to maintain an obedient society. “The government looks after the citizens to a certain degree,” Tekeste says. “People get help so they won’t go hungry, but the assistance is limited.”

Over the years, the government has adopted a series of tough measures to consolidate its tough, centralist economy. For example, no more than $300 a month may be withdrawn from a bank account, and anyone who wants to establish a private business faces numerous obstacles. In the absence of a vibrant private economy, many families depend on aid sent by refugees. In the past, the government made every effort to stop people from emigrating and looked askance at ties with the diaspora. Nowadays, semi-official agencies help arrange money transfers from Eritreans abroad for their families who stayed behind.

The port city of Massawa, Eritrea. Buildings from the Ottoman period and more recent colonial times are falling apart and riddled with bullet holes from the fierce battles of the 1990s.

The port city of Massawa, Eritrea. Buildings from the Ottoman period and more recent colonial times are falling apart and riddled with bullet holes from the fierce battles of the 1990s.

The population must also contend with a serious housing crisis. The large-scale flight did not bring about a reduction in home prices. On the contrary: The combination of the influx of people to the cities and lack of new construction has spiked real estate prices.

“Not one building has been erected in Asmara since 2006,” Abraham Zere, the journalist, says. “Rent has skyrocketed and is no longer consistent with salaries and with the money the bank allows you to withdraw – assuming you have money. So a large part of the economic activity takes place under the table, and people have become dependent on funds sent from abroad.”

Indeed, signs of a construction freeze are apparent on the streets of Asmara. Even though the city was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage list two years ago, decay is obvious beneath the apparent order and cleanliness. The once-lauded, fine Italian-era buildings are peeling and cracked, and have not been renovated for years. This is also the case in the port city of Massawa, where most of the old buildings from the Ottoman period and more recent colonial times are falling apart and riddled with bullet holes from the fierce battles of the 1990s.

While construction is in crisis, other industries are likely receiving encouragement thanks to the involvement of foreign companies. But this is an illusory boom, because much of it is also based on forced labor. Foreign corporations frequently exploit the local workforce through the agency of the army. According to the UN report, Eritrean soldiers have been employed in mining, fishing and industrial enterprises by both foreign and local companies – under shameful conditions. Workers were denied breaks, received inferior food and suffered from poor hygienic conditions. In some cases, workers who wanted to rest were lashed to a pole for the night. A lawsuit is currently underway in Canada against a local company that is engaged in mining in Eritrea. The plaintiffs are exiles who say they were employed in the company’s mine as soldiers.

Listening post

Another method the regime has for subjugating the population is through Afwerki’s divide-and-rule policy. Incarcerations and house arrests are the lot not only of deserters and dissidents, but also of people who have ties to the government or even work for it. These arrests, on trumped-up charges, can take place with no warning or explanation. In some cases, the detentions are short-term, a means of deterrence and warning instituted by the president, but in other cases they are open-ended.

“The system of factionalism and arrests has created a conflicted hierarchy,” Tesfai says, “and today there is no publicly accepted leader who could replace the president. If Afwerki falls, we will probably see a civil war here. For that reason, our goal is not to topple the president but to put pressure on him to change his policy, in part through foreign entities that maintain ties with Eritrea.”

Israel is one of the foreign actors active in Eritrea – which is essentially isolated in the international community – although the nature of these bilateral ties and their impact is not clear. Indeed, the Jewish state has maintained diplomatic relations with the African nation since its founding in the 1990s. Unlike other states, Israel’s ties with Eritrea are not necessarily economic in nature, but rather security related. Over the years there have been reports that Israel has been allowed to anchor maritime vessels at an Eritrean port and to operate a surveillance station as well, as part of its effort to scuttle arms smuggling from Iran to Hamas and Hezbollah.

Though it is well aware of the political situation in Eritrea, Israel continues to maintain relations with its dictatorial regime. Last summer, the state was compelled to respond to a petition submitted to the High Court of Justice on behalf of human rights activists by attorney Itay Mack, who is dedicated to exposing information about Israel’s arms- and security-related deals with other countries. The petition demanded that an opinion drawn up by the Foreign Ministry about the situation in Eritrea be made public. The court noted that the documents paint a worrisome picture of the human rights situation in the African country, but rejected the petition on the grounds that “additional interests, among them the effort to avoid damage to Israel’s foreign relations, also deserve protection.”

In the meantime, Eritrea’s future remains cloudy. There are incipient signs of a new openness, such as the peace agreement with Ethiopia, a flow of tourists and the lifting of a UN-imposed arms embargo. But at the same time, there is little evidence of an improvement in the human rights situation, of a reduction in the mass arrests or of a revision of the policy of indefinite military service. Tesfai, the underground member, refuses to give up. “We intend,” he says, “to go on trying to change the situation from within.”

An aerial picture taken on July 21, 2018 shows a view of the Eritrean capital, Asmara with the St. Mary Cathedral tower. Maheder Haileselassie Tadese / AFP

An aerial picture taken on July 21, 2018 shows a view of the Eritrean capital, Asmara with the St. Mary Cathedral tower. Maheder Haileselassie Tadese / AFP

Eritrean President Isais Isais Afwerki. Photo: AFP

Eritrean President Isais Isais Afwerki. Photo: AFP Eritreans migrants walk through a road on the Ethiopian side of the Ethiopia-Eritrea border. Photo: AFP

Eritreans migrants walk through a road on the Ethiopian side of the Ethiopia-Eritrea border. Photo: AFP

A photo taken on July 22, 2018 shows a general view of Old Massawa with the port and the train tracks that leads to the Eritrean capital Asmara.

A photo taken on July 22, 2018 shows a general view of Old Massawa with the port and the train tracks that leads to the Eritrean capital Asmara.