Source: Washington Post

The deadliest killings occurred at the Mirab Abaya prison camp, where current and retired Tigrayan soldiers were detained

December 4, 2022 at 2:00 a.m. EST

Then the killings began.

By sunset the next day, around 83 prisoners were dead and another score missing,according to six survivors. Some were shot by their guards, others hacked to death by villagers who taunted the soldiers about their Tigrayan ethnicity, prisoners said. Bodies were dumped in a mass grave by the prison gate, according to seven witnesses.

“They were stacked on top of each other like wood,” recounted one detainee who said he saw the aftermath of the slaughter.

The massacre at the camp near Mirab Abaya, which was covered up and has not been previously reported, was the deadliest killing of imprisoned soldiers since the war started, but not the only one. Guards have killed imprisoned soldiers in at least seven other locations, according to witnesses, who were among more than two dozen people interviewed for this story. None of these incidents have been previously reported either.

The dead were all Tigrayans, members of an ethnic group that dominated the Ethiopian government and military for nearly three decades. That changed after Abiy Ahmed was appointed prime minister of Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most-populous nation, in 2018. Relations between Abiy and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) quickly nosedived. War broke out in 2020 after Tigrayan soldiers in the Ethiopian army and other Tigrayan forces seized military bases across the Tigray region.

Fearing further attacks, the government detained thousands of Tigrayan soldiers serving elsewhere in the country. They have been held in prison camps for nearly two years with no access to their families, phones or human rights monitors. Other Tigrayan soldiers were disarmed when war broke out but continued working in office jobs. Many of them were detained in November 2021 as Tigrayan forces advanced toward the capital, Addis Ababa.

Most of the killings, including the massacre at Mirab Abaya, happened then. Prisoners speculated the attacks might have been triggered by fear or revenge. None of the soldiers killed had been combatants fighting against the Ethiopians and thus prisoners of war.

In some prisons, senior Ethiopian military officers either ordered the killings or were present when they occurred, prisoners said. Elsewhere, imprisoned soldiers said they continue to be guarded — and beaten — by those who killed their comrades.

While there is little sign that the killings were centrally coordinated, there is evidence of widespread impunity. Only in Mirab Abaya did officers intervene to stop the killing.

These newly revealed details come as both sides in the conflict are hammering out details of a cease-fire, announced last month, that has been met with suspicion among the population over a range of issues, including whether there will be accountability for war crimes and other atrocities. How the government responds to the revelations of prison killings could suggest how it will treat other abuses allegedly committed by security forces.

The witness accounts also illuminate how the ethnic divisions tearing at Ethiopia’s society are also eroding its military, once widely respected as one of the region’s most professional and still often relied upon by Ethiopia’s neighbors to help keep the peace. Many of those killed in the prisons were among the thousands of Ethiopian troops who have served in international peacekeeping missions under the United Nations or African Union.

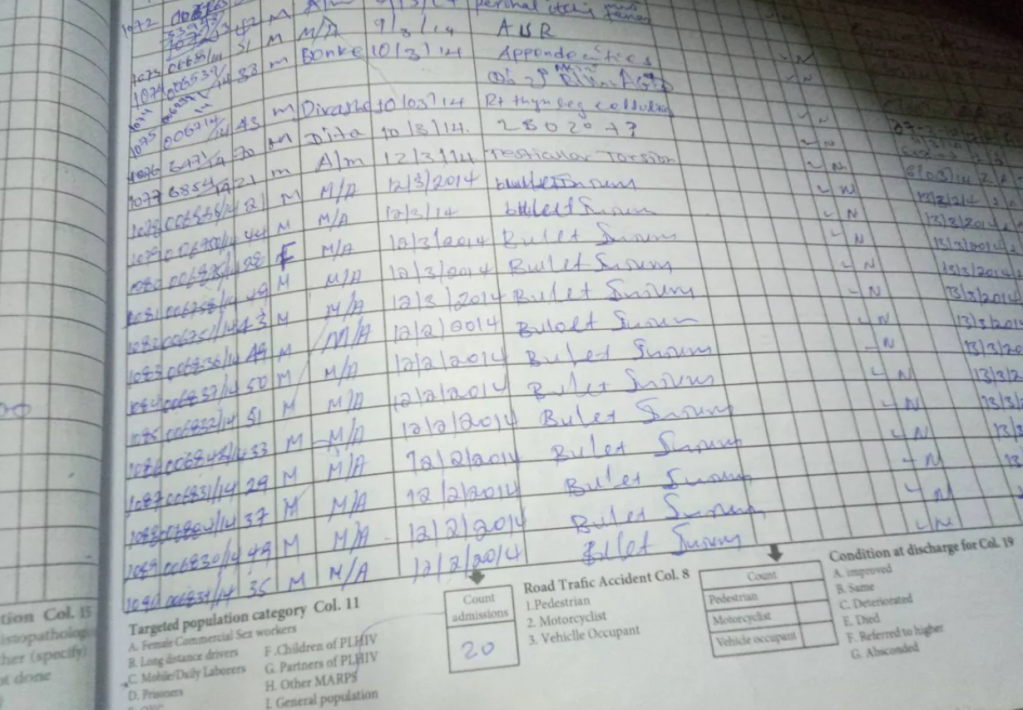

This article’s account of the bloodletting is based on 26 interviews with prisoners, medical personnel, officials, local residents and relatives, and on a review of satellite imagery, social media posts and medical records. Two lists of the dead were provided separately to The Washington Post, and both included the same 83 names. The identities of 16 victims were verified during interviews with detainees. All witnesses spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals.

When asked about these accounts, Col. Getnet Adane, a spokesman for the Ethiopian military, said he was too busy to comment. A government spokesman and the prime minister’s spokeswoman did not respond to requests for comment. The state-appointed head of the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, Daniel Bekele, said the panel was aware of the incident and had been investigating it.

Bullets and machetes

About 2,000 to 2,500 serving or retired Tigrayan soldiers, both men and women,were being held at the new prison camp about half an hour’s walk north of the town of Mirab Abaya, in a sparsely populated area dotted with banana plantations and near a large, crocodile-infested lake. Some buildings were so new they didn’t even have doors. But the camp hadguard towers and demarcated boundaries. Guards told prisoners they would be shot if they crossed the line.

In mid-November 2021, a new prisoner — a just-married major who worked in the military’s defense construction division — was badly injured by guards when he went outside his cell at night to urinate, six other detainees said. He was beaten badly. Some said he was shot in the stomach. Guards later told prisoners that he died on the way to the hospital.

Over the following days, tensions continued to mount with reports —later confirmed by rights activists — that Tigrayan fighters in Ethiopia’s northern Amhara region were killing and raping as they advanced toward the capital.

But on Nov. 21, the Mirab Abaya camp seemed calm, prisoners said. Many had been basking in the late afternoon sun when between 16 and 18 guards opened fire.

One prisoner said that he had been near two women when they were shot in the toilet.

“One woman died immediately, and the other was calling out, ‘My son, my son!’ Then they fired another bullet, and she died,” hesaid. “They [the guards] wanted to kill everyone there.”

One of the women was a major in the Ethiopian ground forces. She was around 50, had served as a peacekeeper in Sudan and had a son and a daughter, according to the witness. Other detainees said the second woman had worked in the Ministry of Defense.

A senior Tigrayan officer said he was inside his cell when he heard gunshots. He stuffed clothes and belongings into a bag. He decided to run if he could.

“I was thinking: ‘Will I ever see my kids? See them succeed in school and have the good things of life?’ ” he said. If he couldn’t run, he would fight, he said. He and his cellmates looked for a stick or anything else to use as a weapon.

A third prisoner said he began to pray.

Not all guards took part in the killing. A fourth prisoner described one guard taking up a position outside the cells and telling the attackers he would shoot them if they came for the detainees inside. That guard was crying, the prisoner said, and was inconsolable for days afterward. Another prisoner said some guards had tried to disarm the attackers.

Yet another prisoner said he was having coffee outside when shots rang out. Like many others, he ran into the surrounding bush. Ethiopian soldiers pursued his small group, he said. After running more than an hour, he said, they saw some locals. The prisoners blurted out that they’d been shot at and begged for help.

“They said … ‘We will show you what you deserve.’ And then they attacked us,” he said.

A crowd of about 150 to 200 people hacked and bludgeoned the escapees with machetes, sticks and stones, he recalled. Most were killed as they begged for mercy, he said, adding that he was hurt badly and left for dead. During the attack, he said, he saw other prisoners run into the lake to escape the mobs.

Other detainees confirmed that there had been machete attacks on those who escaped the prison. They said residents screamed abuse at the escapees and had incorrectly been told they were prisoners of war and to blame for the deaths of local men in the military. Two prisoners said the attacks continued into the next day.

The shooting at the prison stopped an hour or two after it began when Col. Girma Ayele of the Southern Command arrived. By then, prisoners said, the camp was littered with the bodies of the dead and the earth slick with blood. Girma could not be reached for comment.

The Dejen division

The massacre inside the prison was committed by about 18 guards, including a woman, said the six prisoners at Mirab Abaya who were interviewed. These guards and just over a third of the victims came from the same unit: the Dejen army division, formerly known as the 17th Division. It’s stationed in Addis Ababa.

Many Tigrayan soldiers speculated during interviews that the attack was motivated by revenge. Most of the guards who did the killing were from the Amhara region, which Tigrayan forces had invaded as they pushed toward the capital.

Girma told the prisoners these guards were not under his direct control and had been arrested, detainees said. The guards’ status could not be confirmed. The prisoners never saw them again.

A day after the killing, an excavator dug a mass grave just outside the main watchtower at the entrance gate, perhaps 200 meters from the road, according to the six prisoners.

Among those buried was Maj. Meles Belay Gidey, an engineer passionate about his teaching job at the Defense Engineering College. When Meles was serving as a U.N. peacekeeper in Abyei, a disputed area between Sudan and South Sudan, he video-called his two teenage sons and his stepdaughter every evening to talk to them about school, a relative said.

A local resident traveling past the prison camp the next day said the military warned passersby not to take pictures of the grave.

In Mirab Abaya town, officials used loudspeakers mounted on cars to warn the local population that escapees should be killed. The local resident said he saw three or four people attacked near a banana grove and about a dozen bodies bleeding in the streets, some scattered near the church of St. Gabriel. Ethiopian soldiers nearby did not intervene, he said.

The resident also said he saw a man in his mid-20s being beaten by a mob. Both of his hands had been cut off, and his legs were bleeding. The man begged to be killed as he was dragged up and down the street, the resident said. The attackers told the man they would kill him as slowly as possible. Eventually, he was dragged to the camp gate and shot. Another body was being dragged behind a motorbike, the resident said.

“I couldn’t do anything because I feared for my life,” he said.

Ethiopian soldiers take strategic city in Tigray amid civilian exodus

Wounded Tigrayans were taken to three hospitals, survivors said: Arba Minch General Hospital, Soddo Christian Hospital and another hospital in Soddo. Two medical professionals at Arba Minch General Hospital described an influx of patients around 9 p.m. on Nov. 21. One worker shared medical records showing that 19 patients were admitted with bullet wounds and that 15 were discharged the next day. Two died in the hospital and four were dead on arrival, the two medical workers said.

Most of the patients were kept for only a few hours despite life-threatening wounds, the two said. The patients were kept under police guard, both medical professionals said, and they described nurses and other medical staff taunting the wounded about their ethnicity.

Killings in other prisons

Mirab Abaya was not the only prison where imprisoned soldiers were killed. Current and former prisoners said in interviews that they had witnessed guards killing prisoners at Garbassa training center and the headquarters of the 13th Division in the eastern city of Jigjiga; in prisons in Wondotika and Toga near the southern city of Hawassa; in the southern area of Didessa; and at the Bilate training center in the south. Many of the victims had served as peacekeepers in U.N. missions in Sudan, Abyei or South Sudan or as part of an African Union force in Somalia.

At Wondotika, a detainee said guards had killed five prisoners at facility that holds hundreds of soldiers who are mostly special forces or commandos. The victims included Gebremariam Estifanos, a veteran of a peacekeeping mission in Abyei and an African Union mission in Somalia, who was beaten to death Nov. 8, 2021, in the presence of a colonel and lieutenant colonel from the 103rd Division, a prisoner said. Gebremariam’s biggest wish had been to buy his family a house and his father an ox, the prisoner said. Two other detainees confirmed the account, saying guards often taunted the prisoners about the incident.

Both said that guards had often forced prisoners to dig their own graves, telling them they would soon be killed. The four other soldiers were killed later in November, shot so many times that their bodies were torn to pieces by bullets, the first prisoner said.

“We are beaten and threatened. We have served our country with honor and dignity,” that prisoner said. “I regret my service.”

In Toga prison, guards beat and then shot two Tigrayan soldiers on Nov. 4, a detainee there said. A second prisoner held at Toga, a former peacekeeper who served in Somalia, confirmed two killings. In Garbassa, two prisoners said six detainees had been killed and others injured so badly they had lost the use of limbs and eyes.

“I have seen the bodies being dragged from their rooms,” said a detainee there.

Three prisoners — one from the presidential guard and two from the Agazi commandos — were killed in July 2021 in Bilate training center after guards accused them of attempting to escape, said a witness previously held there. He described soldiers shooting at their bodies long after they were dead and throwing the corpses outside for the hyenas. And in a detention center near Didessa, near Nekemte town, at least five soldiers were killed and 30 others taken away and never seen again, a prisoner previously held there said.

He broke down as he listed the names he could remember. “I’m so sorry, they were my friends,” he said.

An airstrike on a kindergarten and the end to Ethiopia’s uneasy peace

Two imprisoned soldiers, accused of having mobile phones, were also killed by guards at a detention center in eastern Ethiopia between Harar and Dire Dawa, a witness said.

The imprisoned Tigrayan soldiers interviewed by The Post say none of them have had access to the International Committee of the Red Cross. Until a few days ago, their families had no idea what had become of them. At the end of October, the families of some soldiers killed in Mirab Abaya were informed about their deaths. Several relatives were told their loved ones had died honorable deaths in the line of duty. No other details were given.

Some of the survivors of the Mirab Abaya massacre who are still held there said they fear another outbreak of violence.

“I have a prayer book,” one prisoner there said. “Every day I pray to Mary to see my family again.”

NAIROBI — The scent of coffee and cigarettes hung in the hot afternoon air in a makeshift Ethiopian prison camp, prisoners said, as detained Tigrayan soldiers celebrated the holy day of Saint Michael in November 2021. Some joked with friends outside the corrugated iron buildings. Others quietly prayed to be reunited with families they had not seen in a year, when conflict erupted in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region.

Redwan Hussien , middle, briefing diplomatic community in Addis Ababa on November 5, 2022 (Photo : Public Domain)

Redwan Hussien , middle, briefing diplomatic community in Addis Ababa on November 5, 2022 (Photo : Public Domain)